When he was still campaigning a few months back, Rodrigo Duterte did not promise a lot of things for the science sector.

His rivals who were deep in policy and details did.

His rivals committed to raise R&D expenditure to the ideal 2% of the GDP. He didn’t. The other candidates laid down a list of solutions for the welfare of Filipino scientists. He didn’t.

For all the generalities about his policies, Mr. Duterte said one thing the other presidentiables missed out: too much concentration of R&D resources in Metro Manila with the implication that innovation benefits only the few.

Mr. Duterte is right. Much of the innovation activities are actually happening in the three most prosperous regions—National Capital Region, Central Luzon, and Calabarzon account for 80% of the total R&D expenditure. Soccksargen, Caraga, and ARMM, the three poorest regions, altogether had 1% of the total R&D expenditure.

The disparity is just too extreme that the richest group spent 73 times higher than the poorest one. Mr. Duterte wants to address this, and he wants to do something bold.

“The science initiative must be distributed to the regions, especially where food production needs to be improved, where industry needs to grow, and where innovation needs to be developed.” – President Rodrigo Duterte

He envisioned “stronger R&D in the regions, not just in Manila.”

Mr. Duterte, it seems, is making good on that promise. His choice of Secretary of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) is an early indication.

Fortunato dela Pena is a technology advocate and scientist who has come “from the ranks” of the agency. His appointment to Duterte’s Cabinet has been read as a signal of the DOST’s return to its roots in research and development.

“My top priorities will be on R&D to address pressing concerns on health, agriculture, and the process industries,” said Mr. dela Pena, who submitted his curriculum vitae to the incoming President on the insistence of a Davao-based colleague.

Mr. Duterte told him that ordinary citizens should feel the services of the government.

WHAT IS TO BE DONE

There is a revolutionary character to Mr. Duterte’s ascension to power. His victory represents the people’s renewed hope, trust, and confidence in government to improve their lot. “Change is coming,” his campaign said, and a thirsty nation opened their mouths to the skies.

As Mr. Duterte takes his oath as the 16th President of the Philippines, he carries with it the enormous task of wielding science and technology for promised development. The public now awaits a concrete plan from Mr. Duterte, who said he would “expand R&D initiatives by providing more grant through DOST’s sectoral planning councils in cooperation with universities in the regions.”

To be sure, his S&T agenda is a tall order. It won’t be easy to achieve in a short period of time or within the time his term allows. But it’s certainly doable, and it’s the right thing to do. It should also be done right now.

There are various ways to make his agenda work, as the growing body of local literature tell us. Solving this “R&D gap” will mean raising R&D spending so that the additional resources can go directly or spread to innovation-inactive geographies.

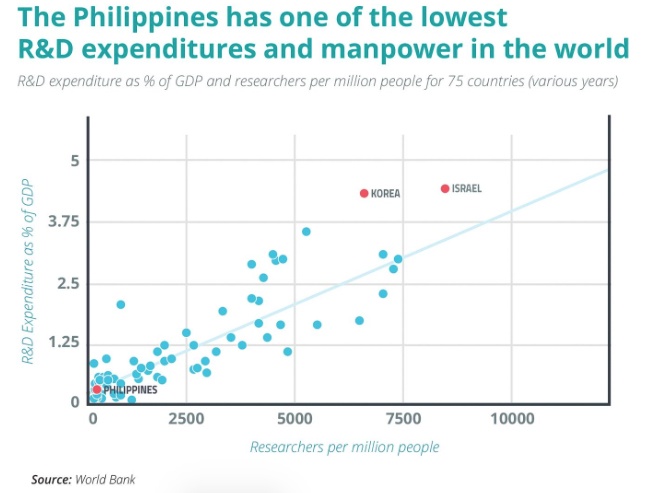

Bigger R&D investment is not the end-all, be-all plan, of course, because current evidence suggests that economies with higher R&D spending tend to have more researchers involved in R&D. Mr. Duterte has to draw up a catch-up strategy, and he needs to train more researchers in areas outside Metro Manila.

The president also has to ensure that the universities, the birthplace of knowledge and innovations, can handle the influx of grant money and researchers in the years to come. In the Philippines, there’s little appreciation on the special role of universities in creating new knowledge. For far too long, universities have been too focused on their “teaching” mission.

So for his partnership with universities to be fruitful, Mr. Duterte has to start building a number of research-intensive universities, especially in Visayas and Mindanao.

BOOST R&D SPEND

Over the past decades, the country’s R&D spending has been way below the ideal—and as a result, it has one of the the lowest R&D expenditures and available manpower among emerging economies. Thus, the first order of business for Mr. Duterte is to provide more funding for R&D.

Against the backdrop of an election victory propelled by populist rage, it’s too tempting to be ambitious and reach the ideal scenario right away. But as the new president may soon find out, it’s better to set a prudent target that can get us closer to the ideal in the next two decades. Part of the reason why the 2% target is hard to attain by 2022 is that the president is coming from a very low start. This year, public sector’s R&D expenditure is estimated at 0.08%.

With a 1% target, the government’s R&D budget will need to increase by 233% to an estimated P37.9 billion next year to reach the target by 2022. If Mr. Duterte aims for a 2% target, the budget will have to rise by more than 1,000% to P164.6 billion in 2017 from the current budget. Such annual increase, to say the least, is unusual in Philippine budgeting, one that’s hard to maintain in the long run.

BUT DON’T PUT THE CART BEFORE THE HORSE

A sudden deluge in funding can also present more problems rather than opportunities to many research agencies. As it is, some of them are encountering problems in spending their whole budgets. Some are are failing to transfer technologies to beneficiaries.

Take the case of DOST. Last year, the DOST was allotted P1.4 billion for S&T funding assistance, but about 20% of this budget was not obligated. What this means is that DOST failed to use about P290 million already allocated by the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) for 2015.

Some research agencies do not operate well. Agencies like the Food and Nutrition Research Institute couldn’t transfer their technologies on time. Some projects had not been operational after they were completed, as in the case of the locally fabricated Automated Guideway Transit funded by the Metals Industry Research and Development Center.

What the data indicates is that increasing the R&D budget by itself won’t necessarily make things easier for government agencies, many of them hobbled by chronic inefficiencies—not discounting corruption.

Once they reach their full capacity to operate, they would ironically become less efficient: they spend less because they run into operational problems like procurement delays, among other concerns.

While it would seem that giving out more money to budget-deprived agencies may translate to more research undertakings, conventional wisdom also tells us not to put the cart in front of the horse. Too much money may simply overwhelm research agencies.

A reasonable approach then would be not to give research agencies budgets way more than they are used to. They would be more efficient when the increase depends on their performance.

WALK BEFORE YOU RUN – 0.5% OF GDP IS FEASIBLE

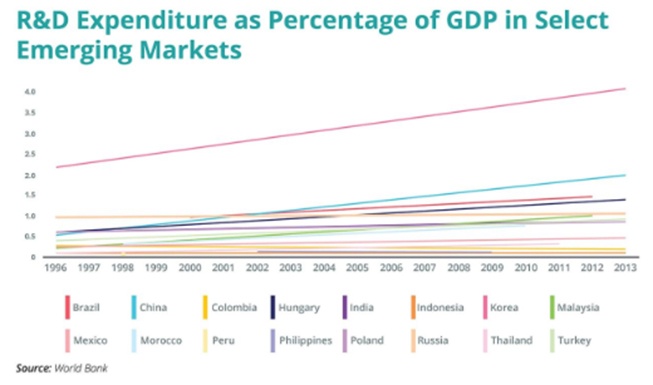

The experiences of other countries also tell us that six years is not nearly enough to reach the ideal 2%.

Some emerging economies like China took about two decades to reach their R&D spending equivalent to 1% or 2% of the GDP. A few such as Russia have remained within 1% of the GDP for about two decades. There are also those economies like Thailand that started at 0.1% of the GDP 20 years ago, but have yet to reach at least 1%.

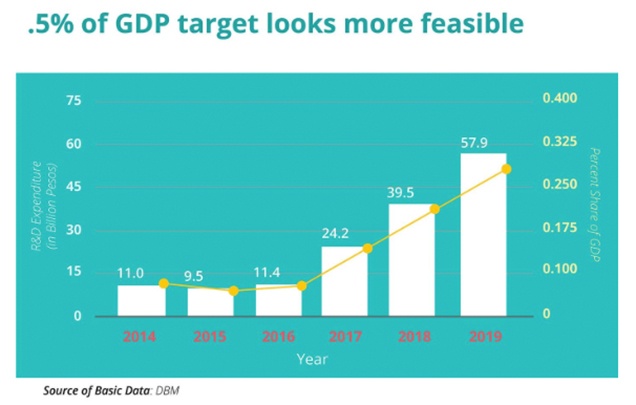

Thus, a target of 0.5% of the GDP looks more feasible within six years, considering the weak spending capacity of research agencies and the historical 20-year growth pattern observed in some emerging markets.

Assuming Mr. Duterte would like to reach 0.5% target by 2022, the current R&D budget will have to rise by 112% to P24.2 billion in 2017, increasing to P39.5 billion in 2018, and going in at P57.9 billion in 2019.

But whatever he decides in the end, one thing is crucial: Set a concrete investment target, and then go hammer and tongs at bringing R&D agencies to full operational efficiency by instilling a new work ethic and culture.

BUILD MANPOWER BY ORDER OF MAGNITUDE

Mr. Duterte himself acknowledged that one of the biggest problems in R&D is manpower.

The Philippines, he said, is a good training ground for scientists, researchers, and technologists. But they are often lured to work abroad in spite of restrictions in their scholarship programs or they sell their patents to foreign corporations.

“We are not able to harness the potential and build the needed knowledge capital.” – President Rodrigo Duterte

Mr. Duterte is not the only one who holds this observation. Over the past decades, researchers have long pointed out the wide manpower gap.

“The most important element in building R&D capability is human resource,” said Reynaldo Vea*, president of the Mapua Institute of Technology, who studied local academe-industry R&D collaboration in 2014. The available manpower should be increased by “an order of magnitude.”

Vea cited that there should be 340 researchers per million people, based on UNESCO benchmark. With a population of about 100 million, the Philippines should have about 34,000 researchers involved in R&D.

The latest count as of 2009 was 13,091.

Assuming the number of researchers would grow in a linear path, the gap won’t be closed over the next 20 years. This forecast offers a grim future, but it also indicates that a catch-up plan is in order.

Extrapolating from the 2009 figure, the number of researchers would grow to 18,742 this year. From this base figure, the pool should grow annually by an average 9% to reach the benchmark by 2025, around 7% to hit the benchmark by 2030, and about 5% to get to the target by 2040.

By the time Mr. Duterte steps down from office in 2022, there should be ideally between 27,700 and 33,500 researchers.

TECH PATRIOTS

From whence can Mr. Duterte build his army of researchers?

“The Indians in Silicon Valley returned home to Bangalore, with the expertise—and just as importantly their American business connections—to successfully put up India’s version of a Silicon Valley,” Vea says.

There are bright sparks in the Philippine start-up scene too, counting independent companies pushing the new digital tools as a way of life and with it, inclusive growth.

According to Charee Lanza, Head of the People Group at Voyager Innovations, which currently incubates a host of tech-driven solutions and has spun off startups such as PayMaya:

“We are very well positioned as the Silicon Valley for emerging markets. Our own vision of digital and financial inclusion is fueled by the talent and passion of engineers produced by our top universities as well as professionals whom we have repatriated from gainful employment in the US and Singapore to join us at Voyager. What drives them? Patriotism and a genuine excitement given the vibrancy of the local digital scene.”

Foreign-based Filipinos can provide the much-needed expertise, but primarily relying on them may not be a good option. As Mapua’s Vea points out, there are fewer Fil-Am research scientists and engineers, and only few of them have reached top technical and management positions in Silicon Valley.

In the Philippines, homegrown talents should fill the gap.

Which brings us to the next challenge: the relatively small number of students taking STEM degrees. A step-change in science and technology education is most crucial in the entire six-year period of the new administration. Otherwise, it would be hard to catch up since the return to this investment takes a long while.

In the meantime, Mr. Duterte could tap graduates of science high schools. In the next decade the pool could potentially come from the country’s science high schools—if they are “shepherded” towards R&D.

Vea estimated that the combined graduates from science high schools all over the country roughly total to 12,700 a year. He recommended that out of this, selected graduates should be supported all the way through college and graduate school.

Mr. Duterte could also fund massive scholarships program, in particular for PhD degrees. But if he decides to scale up publicly funded scholarship programs, he has to address the recurring problem of the scholars failing to complete their degrees on time or at all, as what audit reports indicate. His government must strictly monitor the scholars, enforcing penalties for the erring students while providing incentives for those who finish on time.

Now with the President raising the R&D budget, so should the number of researchers multiply, harbored hopefully by a greater number of universities across the country that can handle R&D projects.

TRANSCENDING, “TEACHING”, CULTINVATING

In the president’s plan, more funding will go to partner universities. This is Mr. Duterte’s practical solution to how he’s going to redistribute R&D to the regions. Universities will handle research grants, which go through the DOST’s sectoral councils.

In countries like Germany, universities are at the center of innovation. They are training grounds for future scientists and engineers—and more importantly, they are custodians of public science.

But not all universities go deep into innovation. Some universities do teaching while others perform research.

It is the research-intensive universities that are critical in fostering innovation. These universities devote a significant portion of their funding and energy to research, building their reputation around the quality, breadth, and volume of their research work.

In the United States, around 150 of more than 3,000 institutions are research universities. United Kingdom and Japan have 20 each. In the Philippines, most universities can’t be considered “research universities.”

Filipino scientist Michael Purruganan, who is the Dean for Science at the New York University, commented in a previous Stack post: “At the moment, universities are still focused on their teaching mission, and they have not adopted structures and policies that incentivize research.”

Vea noted that the government should invest in building the R&D capability of tertiary schools, suggesting that the government build a number of research universities from among the existing state universities and colleges.

“Public universities are the logical vehicles for such a long-pay-off period investment,” Vea noted. “Such basic research capability will translate into serious capability for industry-academe collaborative work in applied research and development.”

Mr. Duterte has a lot of work to do in the next six years.

Majority of state universities don’t invest so much in R&D. DOST and the Commission on Higher Education prescribe that SUCs should allocate at least 3.5% of their budget to research.

DBM data shows that of the 115 SUCs, only 14 SUCs have allocated budget at least 3.5% or higher for research this year.

Overall, state universities only set aside 3% of their total P49.7-billion budget to R&D. The University of the Philippines accounts for 41% of SUC’s total R&D budget.

Of SUC’s P1.4-billion total budget allocated for the “conduct of research activities,” 43% will go to payment of salaries and wages. Office supplies and training expenses account for 14% of the total budget.

Still, there are promising SUCs poised to become research universities. What may frustrate Mr. Duterte is that most of these promising SUCs are concentrated in Luzon.

Budget data from DBM also shows that six SUCs didn’t set aside budget for R&D, while 28 others spend less than 1% of their budget on research—an indication that basic requirements like laboratories and manpower are severely lacking, if not non-existent, in many of these tertiary schools.

DUTERTECH

Much of the solutions to address SUC’s weak research capability are already laid down in a blueprint called National Higher Education Research Agenda-2 for 2009-2018.

The Duterte Administration should only do better at implementing the blueprint—and that would require understanding beyond the nitty-gritty details of the solutions. Mr. Duterte doesn’t need to get too involved in the technicalities of the projects. His Cabinet can do this job very well.

What’s asked from the President is basic: a vision for an innovation-led development, an affirmation that science is important to prosperity.

It’s true that the short term of six years won’t immediately build an “innovation culture.” It won’t certainly ignite the “golden age of innovation.” But this puts us at a critical juncture where Mr. Duterte can influence how science can play a bigger role in development in the future.

For sure, there are other interests that will compete for state resources and his attention. The urgency of everyday issues may give way to the long gestation of research and innovation.

What should not be lost on the daily grind of governing is that pushing research and development, the bedrock of innovation, demands unflagging political will from the president himself. And it will only come from a president who has the mindset for change but, at the same time, understands what things can be achieved and knows how to get things done.

In the weeks leading to his inauguration—in his off-the-cuff comments, with his pre-presidential actions—President Duterte seems poised to do just that.

Full Disclosure: *Reynaldo Vea is the brother of Orlando Vea, President and CEO of Voyager Innovations, Inc, the digital innovation arm of Smart and PLDT. Stack is Voyager’s thought leadership platform for science, technology, and innovation.